When Marc Jacobs was roped in for the Louis Vuitton gig, the brief from the LVMH honchos was simple: don’t mess with Monogram. Ever the rebel, what did Jacobs do? Why, he messed with Monogram, of course!

Now, that’s the story we all know: how fashion’s hottest commodity at the time – and the youngest designer ever to receive the CFDA’s New Fashion Talent award – bulldozed into the luxury scene at 34… and never quite left.

But what we don’t know is how exactly that appointment came to be.

I ask you to return to the early ’90s for that, dear reader. The Supermodels had just walked down the Versace runway, lip-syncing to George Michael’s Freedom ’90. And in a Vogue spread titled “Grunge & Glory,” writer Jonathan Poneman declared, “Throw out your detergent!”

And with revenues slightly south of a billion euros, Louis Vuitton was a far smaller thoroughfare than the multi-billion dollar multi-hyphenate conglomerate it is today. “There was no editorial on Vuitton. We didn’t even have a place to invite editors to come to see the collections,” recalls former LVMH CEO Michael Burke, “If somebody wanted to see a product, I would take them back to the stockroom at our offices on 59th Street opposite Bloomingdale’s.” Former executive vice president Jean-Marc Loubier echoed Burke: “I never met one journalist speaking highly about Louis Vuitton.”

In the end, what saved the day wasn’t one designer – it was seven. Or what the kids these days would dub a collab.

A Century in the Making

Now, it’s not like it was an entirely original idea.

In 1937, for instance, the avant-gardist Elsa Schiaparelli had joined forces with the surrealist Salvador Dalí to create the Lobster Dress, “Dalí’s bright scarlet crustacean,” writes Outlander, “sprawled shamelessly across Schiaparelli’s delicate silk organza, the kind of garment that didn’t simply dress a woman but transformed her into a walking, breathing work of art.”

Similarly, those Yves Saint Laurent shift dresses from FW65 took cues from Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian’s abstract geometric prints. Heck, Monsieur Vuitton himself was the first to see Monet’s “Impression: Sunrise.” And that was back in 1874!

But Vuitton needed something different up its sleeves for its 100th anniversary celebration of the iconic interlocking LV Monogram. Thus, Loubier, along with then-CEO Yves Carcelle, tapped the seven greatest designers of the day – Helmut Lang, Isaac Mizrahi, Romeo Gigli, Vivienne Westwood, Azzedine Alaïa, Sybilla, and Manolo Blahnik – who were given “truly free rein” and no marketing imperative. “The brief was very, very simple: You can do anything you want, as long as you use the monogram,” says Burke.

Thus – after more than two years of legwork (and as many as 15 meetings with the notoriously erratic Monsieur Azzedine) – the Monogram Centenaire collection was born, featuring the likes of a see-through beach tote (with an attached wallet for that essential bit of logo-love) as Mizrahi’s contribution, a leopard-draped Alma from Alaïa, and a backpack-umbrella from Sybilla.

And throughout the course of eight massive parties – where Naomi Campbell reportedly walked a live giraffe across the stage at Palais de Chaillot – one of the handbag world’s first and foremost partnerships was unveiled.

The first, as it would turn out, of many. Like, seriously many.

The Jacob of All Trades

In fact, it was the first time the staid luggage-maker, favored primarily by its traveling Japanese clientele, was noticed by fashion folks – Anna Wintour attended the Monogram centenary event during couture week in Paris — her first time in doing so – and a six-page spread (complete with a custom-commissioned monogramed coffin-trunk) appeared soon after on the pages of French Magazine Égoïste. Now, the Arnaults wanted more.

Enter – Marc Jacobs.

With the scandalizing Sonic Youth collab that ultimately got him fired from Perry Ellis, not to mention, a tremendously successful namesake label, under his wing, Jacobs was the perfect contender to design the house’s first RTW lineup; Vuitton’s answer to Gucci’s Tom Ford, if you will.

And true to his origins, at the heart of Jacobs’ Vuitton was collaboration.

So, for his first trick, he paired with the artist Stephen Sprouse for a project titled “anti-snob snobbism,” that saw the house’s hitherto untouchable logo translated into the urban countercultural aesthetic, rendered atop the brand’s bestselling Speedys and Almas in sprawling graffiti.

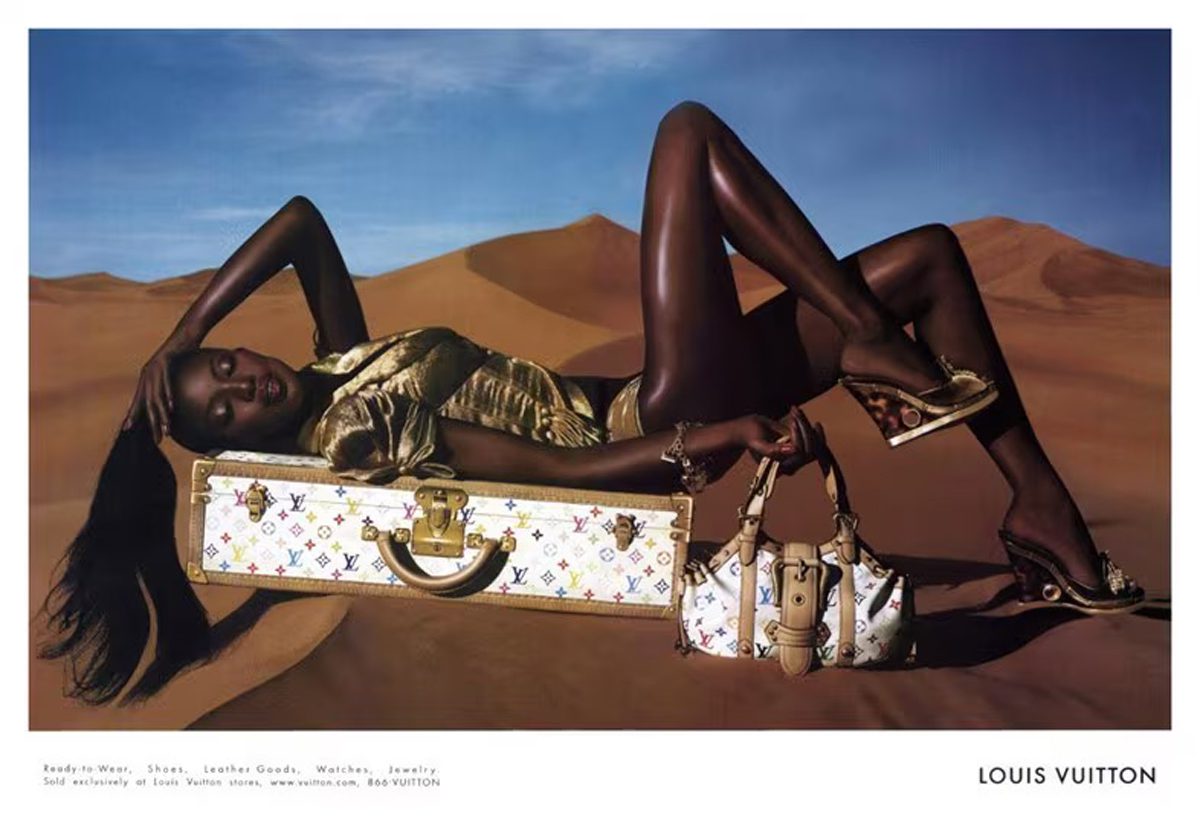

Jacobs went onto pay posthumous homage to Sprouse with the Monogram Roses, while reviving the graffiti print in 2009, this time in blinding neons. With Takashi Murakami, he debuted the Multicolore Monogram on the Spring 2003 runway, followed in rapid succession by the Cherry Blossom and Cerises collections favored by the Paris Hiltons and Regina Georges of the day.

Spring 2008 saw a recreation of the “Nurse” series of paintings by Richard Prince on the Vuitton runway, while in 2012, Yaoi Kusama splashed the maison’s monogram canvas and vernis bags with polka dots.

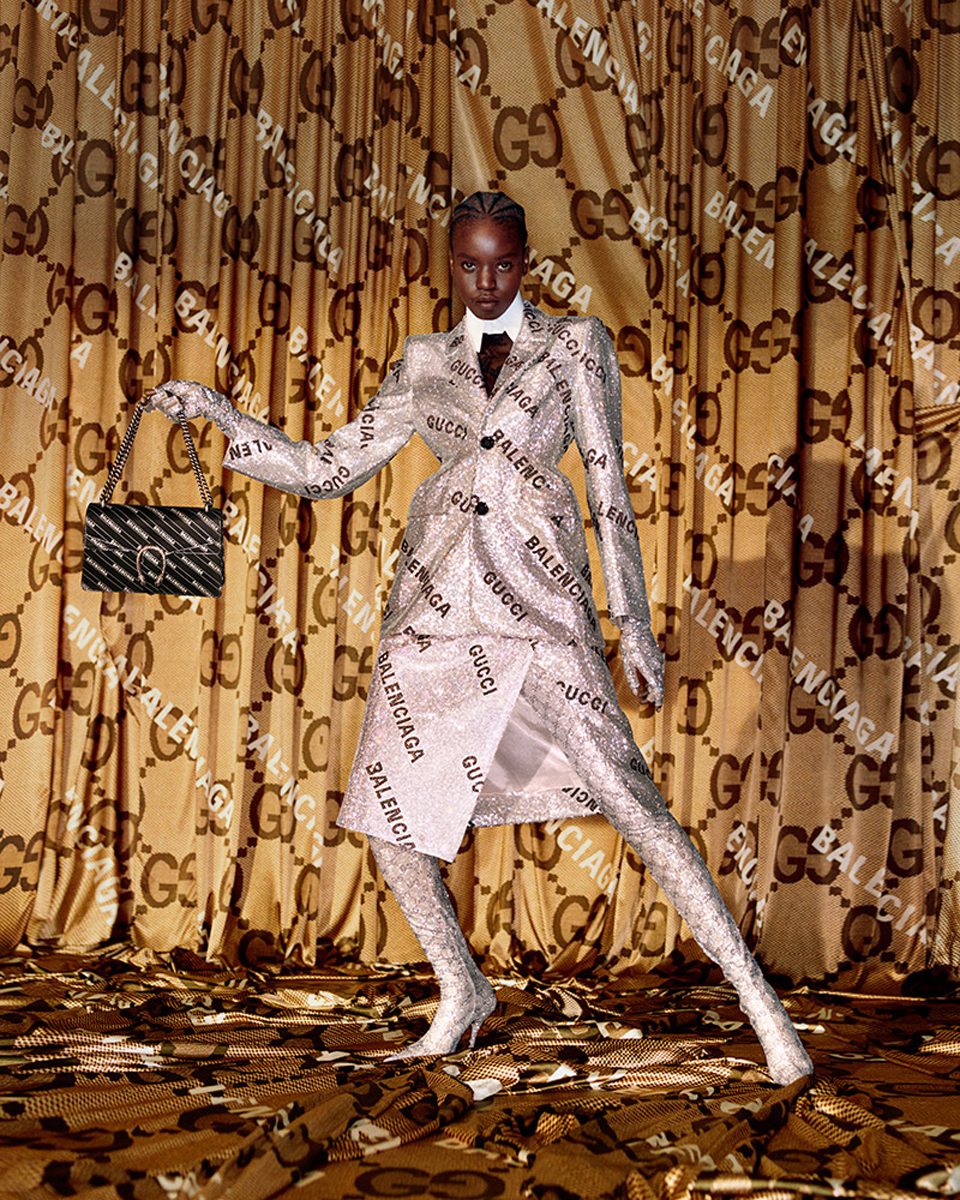

And even though Jacobs departed his post, designer-artist collabs – not just at Vuitton, but also at Gucci, Dior, Fendi, and Loewe – weren’t going anywhere.

From the High Streets to the Balance Sheets

Of course, not all collabs are hits.

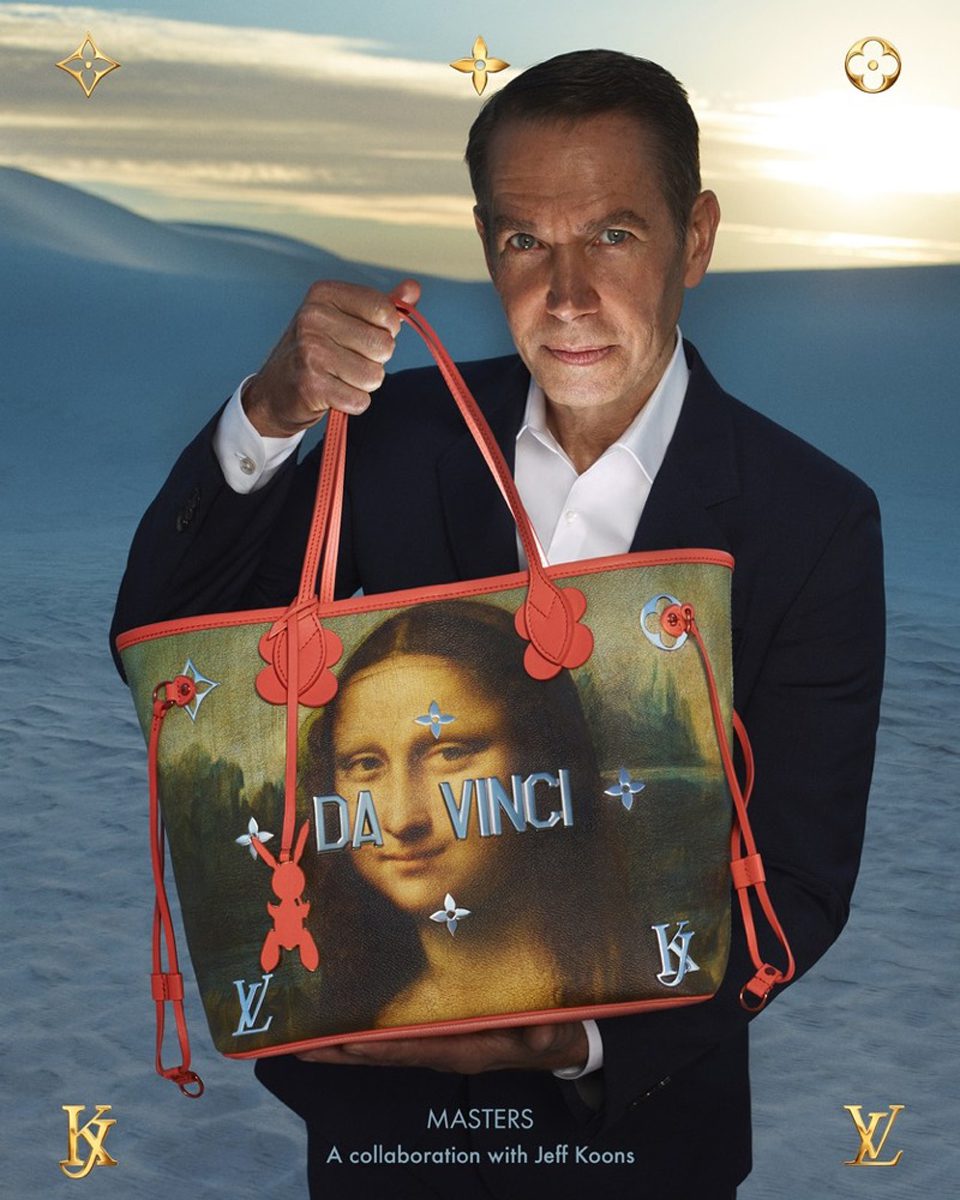

Some, like the one with Jeff Koons, inspired by his 2015 “Gazing Ball” series, saw the likes of Da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” Van Gogh’s “Wheat Field With Cypresses” and Rubens’s “The Tiger Hunt,” reproduced in high-definition detail on Vuitton wares (down to “the cracks in the canvas”), the balls in question replaced by “highly reflective gold or silver letters spelling the artist’s name on the outside like a giant piece of hip-hop jewelry”

Amanda goes on to declare, “They’re bad. They’re, like, disaster-level bad. They’re bad in a way that feels pointedly contemptuous of Louis Vuitton’s customers. It’s over 24 hours later, and my mind is still boggled that they even exist at all.” Which was perhaps the point really, and from Mr. Arnault managed to elicit “a big smile, which is a lot of reaction from him.”

Others, like the partnership between Artistic Director of menswear, Kim Jones, and American streetwear giant Supreme, which saw classic Epi leather bags furnished in the latter’s red and white logo print – and still sell for an arm and a leg – really have no explanation as to their popularity.

Now, as is Koons’ mission statement – to eradicate the elitism of the art world – collabs are a way for the sacred, sanctimonious world of art to reach us mortals, whether by means of a $585 keychain or $4,000 carryall, or if nothing else, “they can walk by the windows of Louis Vuitton and enjoy them.”

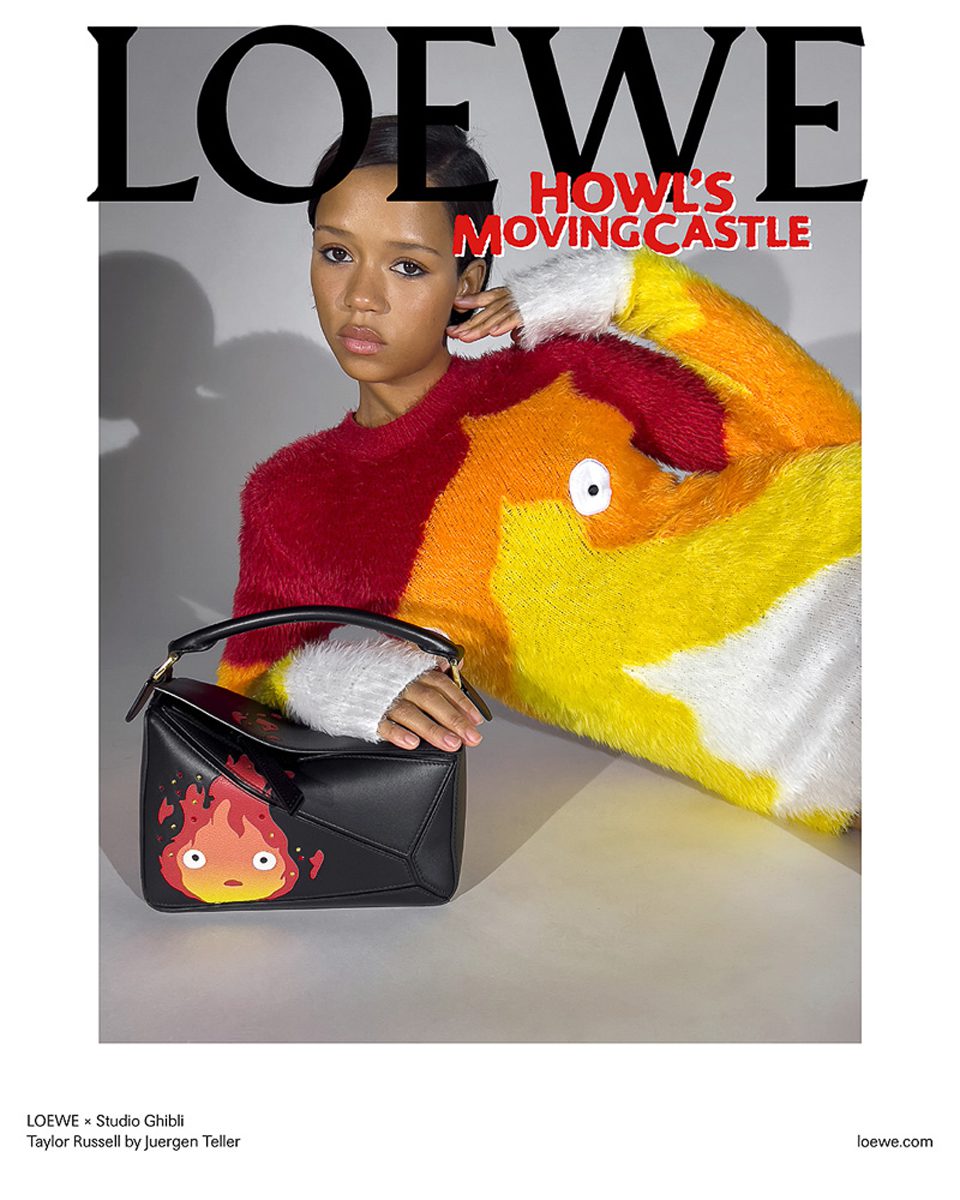

Even if said artist is a Jennifer Lopez (Coach), Hayao Miyazaki (Loewe), or Harry Styles (Gucci HA HA HA).

But more so is the fact that collabs today have become a quick cash-grab, a shortcut to banking on the big fanbases of artists who otherwise have little to do with fashion, with little to no creative contribution from the brand itself.

Russell Peacock, of the American husband-and-wife photography team of Peacock and Hansen that had photographed the original 1996 Centennial campaign, opines: “In the ‘90s, you could actually make fun of fashion to sell fashion. You can’t do that anymore.”

Today, fashion collabs seem to have lost their original purpose as a tool of experimentation and instead morphed into yet another vehicle of marketing. Burke may have been sarcastic when he said, “Art is the domain of the minister of culture, not commerce,” but there’s some truth to it, too.

That being said, though, as an avid lover of all things feline, am I loving that new Louis Vuitton x Grace Coddington collab? Absolutely!