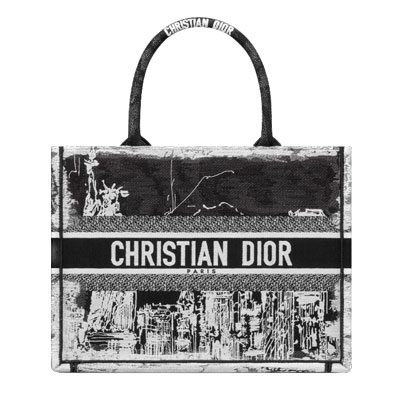

When you pick up a faux Louis Vuitton bag online or at a souvenir shop, do you ever wonder where your money goes? We followed the money to find out what happens to the revenue from counterfeit goods. The myths and realities surrounding the counterfeit market may shock and surprise you.

Myth: Buying counterfeit bags is a victimless crime.

Reality: Counterfeit handbags and accessories may be an inexpensive way to wear the latest luxury bags and trendy accessories. But fakes are the scourge of luxury brands who invest vast amounts of time and money protecting the integrity of their goods with varying amounts of success. In addition to intellectual property theft, brands maintain counterfeit products are inferior to the originals, and most of the time that’s true. However, there’s another reason to reconsider purchasing a counterfeit bag, however chic it may look. While the price of the bag may be comparatively low, the money paid will most likely end up funding organized crime, human trafficking, or terrorist activities around the world.

In 2016, the International Chamber of Commerce addressed the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Center (UNCCT) to discuss the growth of terrorist financing via counterfeiting and organized crime. ICC director Jeffrey Hardy said “Organized crime has deliberately and in great numbers moved into trademark counterfeiting, and copyright piracy – largely due to high profits, low risk of discovery and inadequate or minor penalties if caught, and what started out as a business model for organized crime has now also become a way to finance terrorism.”

Myth: Sales of counterfeit goods don’t amount to that much anyway.

Reality: In May 2019, analytics company Ghost Data studied the level of fake luxury products being sold on the social media platform and found that more than 56,000 accounts were found to be linked to the luxury counterfeit industry. In 2016, the figure was just about 20,000. Ghost Data also reports that the most popular fakes on social media sites are Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Gucci and Nike. The market for counterfeit goods generates an estimated $1.3 trillion dollars and costs luxury brands over $30.3 billion. The counterfeit market has been described by experts as “an enormous business hydra.” If law enforcement, customs agents or border control agencies cut one head off, they find two more in its place. The money counterfeiters make from selling fake goods, online, on the street, from the trunks of cars or tiny storefronts on Canal Street costs governments billions of dollars in tax revenue.

Trafficking in counterfeit goods is attractive because it’s a quick way to raise a lot of money.

Myth: Buying a counterfeit bag hurts luxury sales, but it’s can’t really fund terrorists.

Reality: Investigators have been able to link terrorist attacks to counterfeit goods as far back as the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, the 2004 Madrid subway bombing and most recently the 2015 attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo. Trafficking in counterfeit goods is attractive because it’s a quick way to raise a lot of money. International law enforcement, trade organizations, intellectual property watchdogs, and the United Nations all know terrorist groups fund their endeavors by selling counterfeit luxury goods and are working to stop it.

Background: The Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack was funded by the sale of counterfeit goods.

In January 2015, after the satirical French magazine recently published a picture of the Prophet Muhammad on its cover, two brothers, Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, burst into the magazine’s Paris office and killed 12 people, including a police officer, and injured 12 others. They were caught and killed in a shootout with police.

French authorities later discovered that the brothers, who had connections to several Islamic terror groups, funded their attack by buying and distributing counterfeit goods, including sneakers and cigarettes. According to a report in FinExtra, Cherif Kouachi bought 8,000 Euros ($8,700 dollars) worth of counterfeit items from China, paid for it via Western Union, and then sold them online in France. Several reports also note that the brothers were selling drugs to fund the attack, but moved to counterfeit goods because they are much easier to sell and don’t carry the same harsh penalties if they’re caught. In fact, French authorities had been monitoring the brothers’ activities for three years but stopped in 2014 when they could find no trace of illegal activity other than selling counterfeit trainers, which at the time was not considered a potentially dangerous criminal activity.

Myth: Nobody really knows who these counterfeiters are or where they are.

Reality: International law enforcement is taking on counterfeiters with a variety of methods including new technologies, artificial intelligence and old fashioned shoe leather.

A leader in the field is Dr. Louise I. Shelley. She’s an expert on the relationship between crime and terrorism, a professor at George Mason University and author of numerous articles and books on the subject, including “Dirty Entanglements: Corruption, Crime, and Terrorism” and “Dark Commerce.” Shelley says that when a customer buys a counterfeit handbag, they have more contact with what Shelley terms ‘dark commerce’ than they may realize. The market for counterfeit goods is rising as more and more traffickers turn to technology such as text and social media apps to market goods and transfer cash.

In the December 2017 issue of the NATO Review, Shelley emphasized that proceeds from counterfeit goods help fund not only terrorists but help prop up corrupt regimes: “The Syrian conflict, like many others in the world, has been financed, in part, by illicit trade,” she wrote. “This illegal cross-border trade is dependent on corrupt officials. Smuggling of drugs, humans, oil, antiquities, cigarettes, and other contraband has provided funds to buy weapons and sustain fighters both of President Bashar Al-Assad and of rebel and terrorist groups.”

Counterfeit investigator Alastair Gray has been chasing counterfeiters for more than a decade and has seen counterfeit producers first hand. He’s gone undercover investigating and busting up counterfeit rings around the world, and knows counterfeiting is big business. “These are not street thugs; these are professionals,” he says. “They fly first class.” Gray says the damage that’s possible with the trillion-dollar underground economy is frightening. “Fakes fund terror,” he said. “Fake trainers on the streets of Paris, fake cigarettes in West Africa, and pirate music CDs in the USA have all gone on to fund trips to training camps, bought weapons and ammunition, or the ingredients for explosives. So whatever you think, this isn’t a faraway problem happening in China. It’s happening right here.”

Terrorists are selling fakes to fund attacks, attacks in our cities that try to make victims of all of us.

“What the tourist on holiday doesn’t see about those fake handbags is they may have been stitched together by a child who was trafficked away from her family,” says Gray, who know works with Tommy Hilfiger. “In his popular Ted Talk he says that counterfeiting is not a victimless crime. “Terrorists are selling fakes to fund attacks, attacks in our cities that try to make victims of all of us. You wouldn’t buy a live scorpion, because there’s a chance that it would sting you on the way home, but would you still buy a fake handbag if you knew the profits would enable someone to buy bullets that would kill you and other innocent people six months later?” he asks. “Maybe not.”

Myth: Nothing can stop counterfeiting.

Reality: Counterfeiting can be slowed down.

Experts agree that both luxury brands and their customers can and should take an active role in halting the flow of counterfeit goods that fund illegal activities. Consumers can be careful about where and from whom they purchase luxury goods both online and in person. Brands understandably cautious about entering the secondary market and reselling goods themselves or through channels like The Real Real should consider it one way to stop the flow of goods that both damage their brand and fund terrorism, trafficking, and crime.

However there are experts who believe that luxury brands should invest in increasing their presence in the secondary market either via direct sales or partnerships with certified resellers, it could eventually regulate the resale market. Building confidence in the secondary market could work to lower the number of counterfeits sold, protect their brand, and give customers a more reliable option for obtaining legitimate goods at reduced prices. The Harvard Business Review suggests bringing outsourced manufacturing back home to its founding countries. HBR says this would help brands keep tighter control on production and overruns while and emphasizing the heritage craftsmanship and real value for money.